Subscribe to SCP News

SEMINAR ON THE VALORISATION OF RESIDUES FROM THE PRODUCTION OF OLIVE OIL IN TUNIS

In the context of the launch of the new Tunisian Ecolabel for bottled olive oil, the CP/RAC took part in a seminar on 14 October at the Tunis International Centre for Environmental Technologies (CITET) to look at the different ways of managing olive oil residues. Representatives at the seminar from Tunis included experts from the Ministry of the Environment and Sustainable Development, the National Waste Management Agency (ANGED) and CITET.

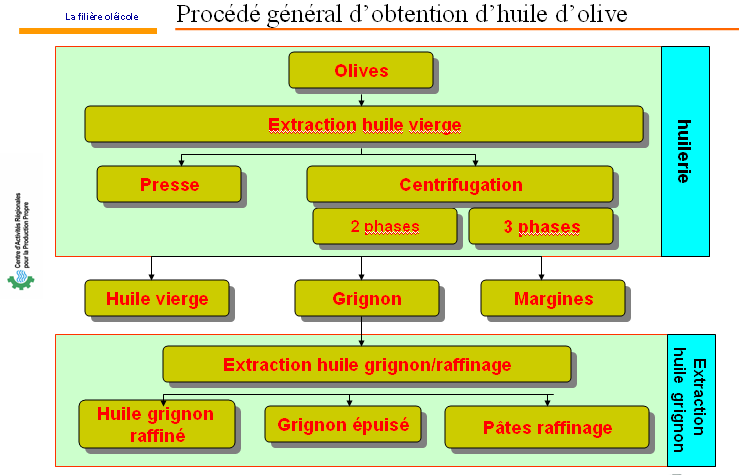

Tunis has more than 67 million olive trees in an area covering 1.7 million hectares, accounting for approximately 80% of the country’s arboriculture. In 2009, 802,150 tonnes of olives and 160,000 tonnes of oil were produced (7% of the world’s olive oil production and 9% of global olive oil exports). Some 70% of the oil is exported, of which 97% is in bulk and 3% in bottles. Exports represent 43% of all exports from the agro-food industry and 5% of Tunisia’s total of exported goods. According to the National Oil Office, Tunis has 1,750 oil mills, 7 factories to extract residual oil, and 40 bottling plants, along with a number of refineries and coal-bunkers. The Director of CITET, Samir Belaid, stressed that it is imperative to identify solutions that are compatible with ecological requirements and that are financially acceptable with regard to valorising residues from extracting olive oil and to reducing the activity’s environmental impact. The recently approved initiative by the Ecolabel Consultative Committee for bottled olive oil was discussed as a means of encouraging companies to adopt clean production criteria and sustainable development practices. Kamel Saidi, Head of Company Services at CITET, went over the methodology used and the technical and ecological criteria applied when preparing the Ecolabel, as well as the main problems encountered during the preparatory committee meetings. A total of 75 criteria were drawn up, of which 57 are compulsory. He highlighted that the two-phase extraction system is considered the most ecological on account of the low volume of residue, and the low consumption of water and electricity compared with other extraction systems. However, obtaining the Ecolabel does not exclude the use of other technologies. To conclude, he presented a CITET pilot initiative working alongside two oil mills that are in the process of obtaining the Ecolabel.

Afef Siala, Deputy Director of the National Waste Management Agency of Tunisia (ANGED), emphasised that, every year, Tunisian oil mills produce an average of 1 million tonnes of olive oil mill wastewater (liquid residue from producing olive oil) - a figure that has increased on account of conversion of mills to continuous extraction - along with some 650,000 tonnes of pomace (pasty residue), approximately 70,000 tonnes of leaves, and some 150,000 tonnes of high-energy-value sludge arising from the extraction of residual oil – making a total of 2,000,000 tonnes of waste from all over the country. This has led the Ministry of the Environment and Sustainable Development to prepare a National Action Plan to manage mill wastewater in order to promote its valorisation.

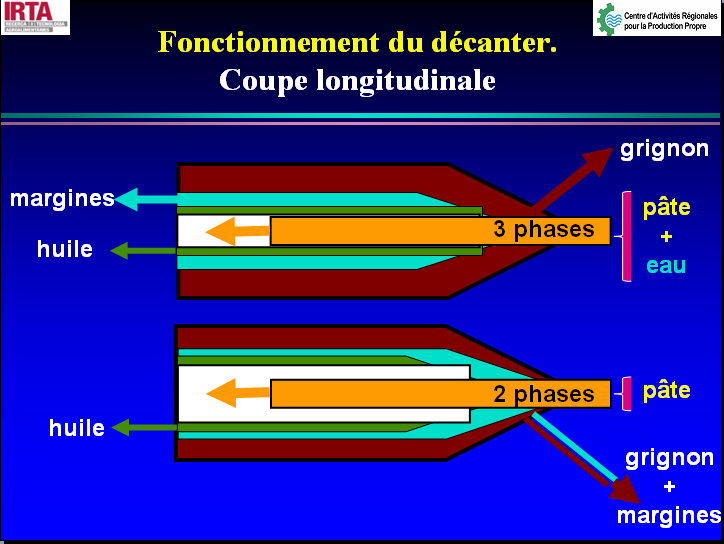

Representing CP/RAC were Frederic Gallo, who presented an introduction to the environmental problems associated with the uncontrolled management of residues from the olive oil industry; Joan Tasias, an expert in managing olive oil residues, who gave a presentation about the various alternatives that are economically viable; Agustí Romero, an engineer from the Institute for Food and Agricultural Research and Technology (IRTA) of the Generalitat of Catalunya, who presented a comparison of the two-phase and three-phase extraction systems; and José María Álvarez, an expert in plants that compost olive oil residues, who presented the composting of olive oil residues as a viable and ecological alternative to traditional waste-management methods (storage and evaporation in pools, as a watering fertiliser, and extraction of residual oil using solvents, etc.) and discussed the experience of the Junta of Andalusia in promoting and constructing composting plants for the olive oil industry. The public that took part – some 60 people – were mostly mill owners and civil servants.

Frederic Gallo highlighted the pollutant potential of the residues produced by oil mills (1 m3 of residues produces the same amount of pollution as 200 m3 of residual municipal water) during the short period during harvesting and grinding olives. Disposing of this residue in the municipal residual water network may cause the water treatment facilities to malfunction since they are not designed to handle such high concentrations of contaminants at the same time. In such cases, the entire treatment process often needs to be shut down. Likewise, it is highly damaging to dispose of the residue in rivers on account of the fact that the natural degeneration process consumes vast quantities of oxygen, causing biological alterations in the environment that makes it difficult for aquatic life to survive. Pouring the residue onto the land also causes significant problems in that, besides contaminating aquifers and wells (which ought to be closed if they are sources of drinking water), it reduces the fertility of the sod not only because of the presence of phenolic compounds that inhibit plant growth but also because it increases salinity and causes other harmful physico-chemical alterations in its natural properties.

photo: contamination by olive mill waste water

In his presentation, Joan Tasias commented that there is an extensive range of technological options available that minimise the impact of managing residues and that can even valorise oil mill waste. However, most of these technologies have not got further than the pilot study stage on account of the costs involved.

He described the characteristics of the residues produced by each extraction system, along with the most common options for their valorisation. In three-phase systems, the options for valorising pomace (semi-liquid residue) are to extract residual oil, use it as fuel, use it as a complement for animal fodder, or to compost it, whilst valorisation options for olive oil mill wastewater include using at as a liquid fertiliser in controlled doses, evaporation in pools, and its use as an additive in compositing.

The same applies to two-phase systems, except the semi-liquid pomace needs first to undergo a drying process, if residual oil is to be extracted, owing to the higher water content of two-phase pomace. Needless to say, this drying process is not necessary if the residue is to be used for composting. In both cases, it is advisable to separate the stones first as they are an excellent fuel.

photo: the separation of the olive stones provides an excellent fuel

In summing up the main points of his presentation, Joan Tasias highlighted the need to look at what is the best residue management system on a case-by-case basis, studying factors such as mill size, their geographical location, the extraction technology used (three-phase, two-phase, etc.), the number of mills in the area, the presence of extractive industries producing olive-pomace oil, the price of oil in the market (virgin, olive-pomace, and low-grade), along with the price of pomace. The three-phase system is recommended for small mills that have enough agricultural land to allow for controlled fertilising or evaporation in large pools owing to the fact that it is not possible to process olive oil mill wastewater at a reasonable cost. On the other hand, the two-phase system is the best way of minimising the problem of residues in all other cases, besides reducing water consumption. The two-phase system can involve improving operations and valorising residues, such as employing a second centrifuge, separating the stones, and composting. Drying the pomace using an electricity cogeneration system and subsequent extraction of oil is only to be recommended for very large mills. Finally, a public aid system is highly recommended as a means of promoting two-phase extraction technology (as happened in Spain via European funding) and in order to ensure that there are processing centres for use by large mills or cooperatives.

In his presentation, Agustí Romero covered the differences, from a technical point of view, between two-phase and three-phase systems, and also looked at the environmental impact of both technologies. From an environmental perspective, two-phase systems are much more preferable because they use less water and minimise residues (almost 70% less in terms of volume and with an 80% lower pollutant potential), and also consume less energy. Liquid residues produced by three-phase technology require large storage pools that, besides posing a risk of leakage into aquifers, are foul smelling, and are also prohibitively expensive for many mills. From an organoleptic point of view, three-phase oil is slightly superior (scoring 7.2 compared with 7.1) but the content of polyphenols (natural antioxidants) of two-phase oil is higher, – i.e. it retains its properties for longer – than three-phase oil. On the other hand, the initial economic investment is greater for two-phase technology than for three-phase technology and the traditional method of valorization of pomace (using solvents in order to extract the residual olive oil) is less beneficial economically on account of the previous drying process needed, given that pomace from two-phase systems has a higher moisture content than that produced in three-phase systems.

José María Álvarez presented the composting of residues from two-phase mills as the most rational and beneficial option for the environment in managing residues arising from the production of olive oil. He pointed out that the Junta of Andalusia’s 2007-2012 Climate Change Action Plan is explicitly based on the re-use in agriculture of agricultural by-products, prioritising composting over energy recovery, and providing public funds for the construction of composting plants and promoting the use of compost. Over the medium and long term, the advantage of compost is that it increases the content of the soil’s organic matter, which is usually low in agricultural land in Mediterranean countries. In this sense, a paradox was highlighted in that many mills have to buy compost (which is expensive and difficult to find) to use on their olive groves whilst, at the same time, they are disposing of pomace, which is rich in organic compounds, by sending it to plants that extract residual oil or to cogeneration plants, both of which options incur transport costs and bring in little revenues for the mills.

photo: Composting becomes the most rational solution for olive mill wastes

As a more direct and more financially viable option for producers with land where residues can be spread, the idea of applying these solid residues (two-phase pomace – alperujo in Spanish) directly to the land without undergoing prior composting was considered. In the end, the Junta of Andalusia discarded the application of residues from two-phase extraction directly to the land as an authorised management system because two-phase pomace has a high-moisture content and is difficult to handle and to control the dosage when applied directly to the soil, thus giving rise to environmental risks such as:

• The potential contamination of underground water supplies.

• An undesirable demand for nitrogen in the soil arising from the high C/N ratio of residues, which may compete with the nitrogen available for olive trees.

• Toxic effects for plantations due to its content in polyphenols.

These risks disappear when a previous composting process takes place. Composting is an aerobic biological process where microorganisms break down biodegradable organic material under conditions where aeration, temperature and moisture are controlled. Two-phase pomace compost contains approximately 80% of the nutrients (nitrogen, phosphor and potassium) extracted by olive harvests from the land. It also has high levels of organic matter (between 30% and 50% on a dry-weight basis) and organic carbon (25%).

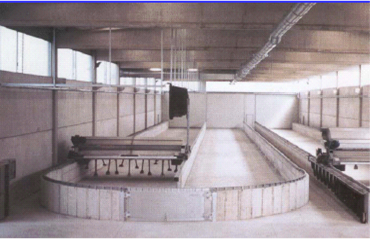

To improve the composting process and its quality, it is advisable first to add to the pomace another residue such as olive leaves, straw, pruning waste, pine bark, etc., as materials to give the compost body, along with nitrogen-rich matter (cattle dung) to balance C/N ratios. To produce compost that is of good quality (stable, and free of pathogens, weed seeds, insect larva and zero phytotoxicity) some 6-10 months are needed - a time scale that matches perfectly to the olive season, thus avoiding the need of boosting the speed of the process. Composting can be open (known as a windrow system), with the use of a front-end loader to turn the compost in order to air it, or closed - the recommended option for volumes in excess of 6,000 m3 per year. Closed systems require a larger initial investment than open systems, although operating costs are lower.

photo: open composting (windrow system)

photo: closed composting system for larger volumes

Compost is applied as an alternative to chemical fertilisers over the whole area between the lines of olive trees, in combination with a ground cover. The main advantages of composting are as follows:

- Large amounts of nutrients are gradually fed to the plants.

- In increasing the content of organic matter in the soil, desertification and soil erosion are avoided.

- There is reduced risk of the soil and underground water becoming contaminated by the inappropriate application of chemical fertilisers used in conventional agriculture.

- There is an increase in the amount of carbon (C) captured by the soil, a process that helps mitigate climate change arising from the emission of greenhouse gases.

- Composting can make a greater contribution than energy recovery to reducing CO2 emissions.

- The use of compost has a preventative effect against fungal infections because it helps make plants stronger – something that has been demonstrated in various studies.

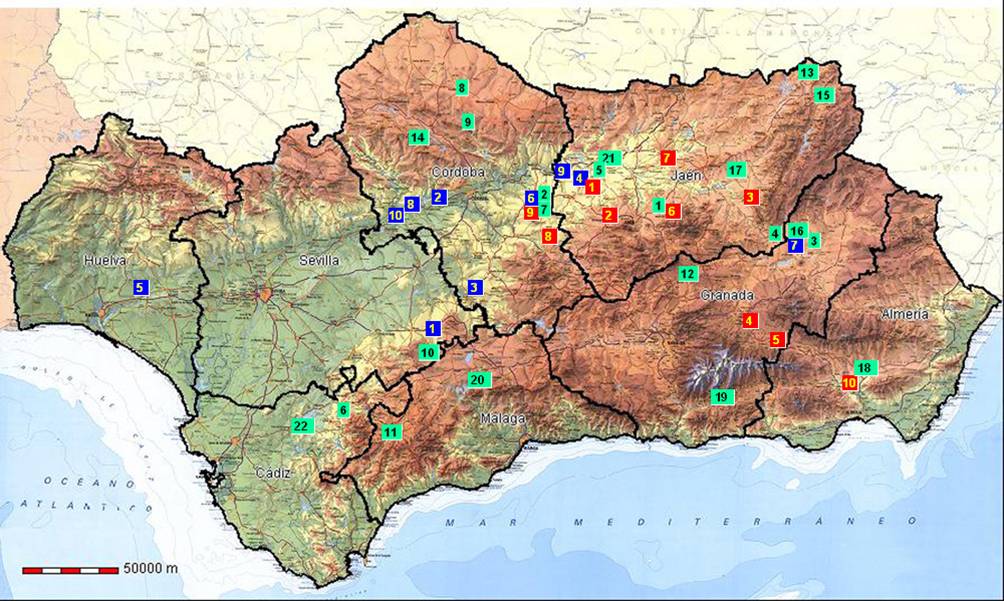

José María Álvarez emphasised that Andalusia has many years of experience in composting two-phase residues and that the Junta of Andalusia offers subsidises of up to 50% of the cost of composting projects. Some 20,000 tonnes of compost are produced by olive mills every year, although that figure is expected to be 5 times higher by 2012. Most of the compost produced is used by olive producers themselves.

graph: location of compost plants of two-phase residues in Andalusia

A 15-year study by the University of Jaén carried out at an olive farm called Cortijo Angulo, which only uses compost obtained from olive residues, found that, compared with neighbouring producers that used chemical fertilisers, there was 400% more organic matter in the soil, 26% greater water retention capacity, 600% more total nitrogen, and 1,084% more phosphor. The farm also achieved carbon fixation of 40 tonnes per hectare, which means that, from a perspective of mitigating climate change, composting is preferable to valorising the energy from pomace. In this sense, it is recommended that the Administration deliver CO2-reduction certificates to those farmers that use pomace compost.

José Maria Álvarez pointed out the collateral benefits of composting that were identified in the Cortijo Angulo pilot study - the recovery of lost soil fertility as a result of erosion, making land available for grazing animals, and an increase in rabbit and partridge populations. It is possible, therefore, to say that the farm was returning to the classic Mediterranean agro-silvo-pastoral system, offering rich biological diversity and soil protection from erosion compared with agro-chemical exploitation that bases productivity on the use of chemical fertilisers.

photo: the return to the classic Mediterranean agro-silvo -pastoral system in opposition to the agro-chemical exploitation relays mostly in the use of compost

photos: The continued application of compost has a reparative effect and prevents soil erosion

In conclusion, José Maria Álvarez highlighted the backing given by the Junta of Andalusia to the composting of residues from olive mills such as organising invitations to submit applications for funding to construct compost plants, holding information sessions, developing composting application technology, monitoring and promoting composting experiences, creating the Composting for Organic Agriculture Working Group of Andalusia as an information-sharing platform for olive mills, the agro-industry, the public administration, research centres, engineering firms and recycling companies.

Frederic Gallo

Chemical Engineer

fgallo@cprac.org

Contacts

CITET (http://www.citet.nat.tn)

ANGED (http://www.anged.nat.tn/)

Frederic Gallo ( http://www.cprac.org/, fgallo@cprac.org )

Joan Tasias (jtasias@agritem.com)

Agustí Romero (http://www.irta.cat, agusti.romero@irta.cat)

José María Álvarez (jose.alvarezpuente@gmail.com)